By Dwight Whitney

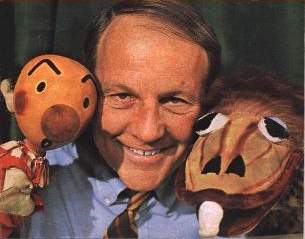

There was a time way back

there in the pre-hippie '50s when Oliver J. Dragon III, an

incurably romantic

hand puppet with one tooth and soulful button-eyes; his

bulb-nosed little

friend Kukla; and their zany "Kuklapolitan" pals were as

big with the short-pants

set as Santa Claus or the giant Popsicle. Kukla, Fran and

Ollie, on which

a whole generation grew up, was the Old Vic of children's

TV shows, and

Ollie its Sir Laurence Olivier.

Ollie

and his friends were the creation of a young puppeteer out

of the University

of Chicago named Burr Tillstrom, who had learned his trade

working for

the old WPA Federal theater project during the

Depression. Fran was

the creation of Fran Allison, a radio star who joined

Tillstrom just before

the original Kukla, Fran and Ollie went on the air locally

in Chicago in

1947. As puppeteer and girl-who-talked-to-puppets,

they managed

to transform 6 o'clock into a magic hour in which children

ceased their

play automatically, and mother's only problem was to avoid

being crushed

in the rush to the television set.

Ollie

and his friends were the creation of a young puppeteer out

of the University

of Chicago named Burr Tillstrom, who had learned his trade

working for

the old WPA Federal theater project during the

Depression. Fran was

the creation of Fran Allison, a radio star who joined

Tillstrom just before

the original Kukla, Fran and Ollie went on the air locally

in Chicago in

1947. As puppeteer and girl-who-talked-to-puppets,

they managed

to transform 6 o'clock into a magic hour in which children

ceased their

play automatically, and mother's only problem was to avoid

being crushed

in the rush to the television set.

Moreover, Kukla became the In thing with the adult community. Tillstrom remembers the week that the show drew 11,000 letters, a substantial part of them from adults. Among the literati a "cult" developed. Thornton Wilder was a constant looker. So were Robert E. Sherwood, Richard Rodgers, Ruth Gordon, Walter Huston, Leland Hayward, Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya. Lillian Gish frequently catted after the performance. John Steinbeck once likened Tillstrom's "writing" techniques to his own. "Our characters could never do anything out of character," Steinbeck said. "They write themselves." By 1951 it seemed that Glue had turned a large segment of the TV audience into knitters. Tiny sweaters, caps, mufflers, nose and tooth cosies (for Ollie's lone tooth) poured in by the hundreds. One viewer even sent a set of false teeth.

This

was all the more astounding because Tillstrom regularly

broke all the rules.

There was no script, only a stream-of-consciousness-type

"inner dialogue"

between Tillstrom and Miss Allison, an idea which was

later incorporated

into a movie, Lili. There was no "production" beyond a

puppet stage. No

concessions were made to anything except "art," a word

which Tillstrom

was not shy about using in regard to himself and his

creations. As

the '50s wore on and "art" was evermore being upstaged by

"commerce," particularly

in the children's field, the networks suddenly had no

place for Oliver

J. Dragon and the other Kuklapolitans. Network

affiliates found they

could do better with animated cartoons. The

hour also conflicted

with the news.

This

was all the more astounding because Tillstrom regularly

broke all the rules.

There was no script, only a stream-of-consciousness-type

"inner dialogue"

between Tillstrom and Miss Allison, an idea which was

later incorporated

into a movie, Lili. There was no "production" beyond a

puppet stage. No

concessions were made to anything except "art," a word

which Tillstrom

was not shy about using in regard to himself and his

creations. As

the '50s wore on and "art" was evermore being upstaged by

"commerce," particularly

in the children's field, the networks suddenly had no

place for Oliver

J. Dragon and the other Kuklapolitans. Network

affiliates found they

could do better with animated cartoons. The

hour also conflicted

with the news.

Recalls Newton ("The Vast Wasteland") Minow, the former FCC Chairman, Tillstrom's friend and greatest admirer, and, incidentally, his long-time attorney: "Anything on TV a long, long time seems to require replacement. I think that's wrong, especially in children's programming."

And die the Kuklapolitans did. It was a quiet death. There was no set villain in the piece. "They" (unnamed network officials) simply could not find a place for the program. NBC let the contract lapse in 1954. ABC, which picked up the show, lost interest in 1957; and Ollie, after 10 years on the air, was a dragon without a lair. "I don't think any of them [the network heads] really understood or liked what we were doing," says Tillstrom. "I didn't want to make it big and noisy." Recalls Pat Weaver, then NBC programming chief: "Burr's history was one of great charm and style, not boffo humor. He was not massively successful in the ratings. One of the difficult things we had to do was to move his show's time slot frequently. Then we had to condense it."

David

Levy, at one time vice president of NBC's programming and

talent operations,

had this to add: "I think he was the victim of a TV

structure that had

to reach the greatest number of people irrespective of

specialized program

content. It went off for the same reason Playhouse 90,

Studio One and The

Voice of Firestone did. These specialized programs

[worked] in the early

days because it was not yet necessary to reach the

tremendous masses.

It may have been too good." Levy added that he was

the man who bought

the show for Life magazine to sponsor. At the time he

worked for Young

& Rubicam. He said he always found Tillstrom

"receptive and ready to

listen but he always made his own decisions. I thought he

was a most unusual

and creative man." said Levy.

David

Levy, at one time vice president of NBC's programming and

talent operations,

had this to add: "I think he was the victim of a TV

structure that had

to reach the greatest number of people irrespective of

specialized program

content. It went off for the same reason Playhouse 90,

Studio One and The

Voice of Firestone did. These specialized programs

[worked] in the early

days because it was not yet necessary to reach the

tremendous masses.

It may have been too good." Levy added that he was

the man who bought

the show for Life magazine to sponsor. At the time he

worked for Young

& Rubicam. He said he always found Tillstrom

"receptive and ready to

listen but he always made his own decisions. I thought he

was a most unusual

and creative man." said Levy.

When Tillstrom left the air, he found no market for his material. If didn't fit into movies or the theater. Clearly no one was going to ask him to play Las Vegas with hand puppets. And no one did. Although he has done three shows for Perry Como, a long-time fan, the other variety shows have shown a lack of interest strange in this era of acute guest-star shortages. He has appeared an Today, done the NBC Children's Theatre, and even won an Emmy and a Peabody (1965) for a series of way-out "hand ballets" he devised during a semiregular stint on That Was the Week That Was. Still he was the Forgotten Man of big-time television. As an "artist" he found it impossible to "adjust" to its requirements.

"No one asks Horowitz to get to the point," lamented Burr the Other day. "Or tells him, ‘You've played piano too long. Why don't you try the bass fiddle?'" Tillstrom is like a man trapped in a bad marriage, because it is the tube that makes the perfect showcase for his talent.

"That's the awful part," he continues. "It's like being in love with a very loud and powerful lady who was once innocent but now drinks too much."

There

have been two important people in Burr Tillstrom's

professional life, The

first was the gentle Fran Allison, married 28 years to a

Motown music publisher.

Fran was playing "Aunt Fanny" on Don McNeill's Breakfast

Club and was a

star in her own right when Burr lucked onto her in

1947. He also

lucked onto Beulah Zachary, a producer at the Chicago

station (WBKB) which

first televised Kukla, Fran and Ollie. Beulah immediately

sensed what Burr

was about. By taking over the business details that were

so odious to him,

she was able to create an atmosphere in which he could

work effectively.

When she was asked what her function was, she

would reply,

"I sweep up."

There

have been two important people in Burr Tillstrom's

professional life, The

first was the gentle Fran Allison, married 28 years to a

Motown music publisher.

Fran was playing "Aunt Fanny" on Don McNeill's Breakfast

Club and was a

star in her own right when Burr lucked onto her in

1947. He also

lucked onto Beulah Zachary, a producer at the Chicago

station (WBKB) which

first televised Kukla, Fran and Ollie. Beulah immediately

sensed what Burr

was about. By taking over the business details that were

so odious to him,

she was able to create an atmosphere in which he could

work effectively.

When she was asked what her function was, she

would reply,

"I sweep up."

Acutely responsive to his needs, she was the one who managed to steer Burr's frail ship through the sharp shoals at commerce. When she was killed in a plane accident early in 1959, it had a devastating effect. He looked around TV and what he saw turned his stomach. "Those little comedies that constantly attack the American male! They're not real. They have nothing to do with love," he complains.

The influx of the machine-tooled television cartoon a lá Hanna-Barbera irritated him. "They've by-passed what TV is really all about for a sloppy marriage between movie house and TV set. There's no room far the creative artist any more. And all the new people coming in are being corrupted. It's a form of drug and it makes for a bad trip."

Beulah's death, along with same family difficulties, dulled his desire to do much of anything about it. He busied himself with commercials, he lectured, he toured women's clubs, and he appeared on TV when asked. He wasn't asked often. Then along came Newton Minow.

Minow,

chairman of the board of educational station WTTW,

Chicago, urged

his old friend to go into ETV. The result: a series

of five half-hour

specials, running for five successive weeks starting Feb.

4, on some 167

National Educational Television stations. Hopefully, says

Ed Morris, programming

head, WTTW, they constitute "just the beginning" of what

might be described

as the resurgence of Oliver J. Dragon.

Minow,

chairman of the board of educational station WTTW,

Chicago, urged

his old friend to go into ETV. The result: a series

of five half-hour

specials, running for five successive weeks starting Feb.

4, on some 167

National Educational Television stations. Hopefully, says

Ed Morris, programming

head, WTTW, they constitute "just the beginning" of what

might be described

as the resurgence of Oliver J. Dragon.

All the old gang are back: Kukla, Fran, Ollie, the man-hungry Buelah Witch, the cultivated Madame Ooglepuss, the stolid Fletcher Rabbit, the gruff Cecil Bill, and Madame Ooglepuss' Southern boyfriend, Colonel Crackie, as well as Ollie's precocious cousin, Delores Dragon. In an early show Ollie takes on the Generation Gap; he and Buelah dress as hippies to find out what hippiedom is all about. Later they discuss civil rights. "When it comes to minorities," Ollie says, "who's more minor than a dragon with one tooth?"

Morris and his producer, Jack Sommers, are giving all this a bright new sheen. The shows are in color, and operate on a budget of $12,000 per show, high when you consider the small-scale sets. There is still no script. "We are very excited," says Morris. "They are great programs, full of innovations from one of the most innovative men ever to grace the medium." Adds Fran Allison, "It was as if we had never stopped doing it at all. I have never seen Burr happier or functioning better."

Already commercial interest in the Kuklapolitans has revived appreciably. In December Burr did a Hollywood Palace, his first ever. In it Ollie talked to his mother in Dragon Retreat, Vt., and sang a duet with Diahann Carroll - "a kind of wild Christmas madrigal thing in Dragon tongue," says Burr.

As

for

his new prospects, Burr takes things calmly. He claims

that he doesn't

need the money and that the important thing is to "do my

thing." And that

he has always done, regardless of whether it had an

audience or not. He

continues to think of himself as "an artist-in-residence,"

whether at a

university or a television network. It's all the same to

him as long as

he is free to work unencumbered.

As

for

his new prospects, Burr takes things calmly. He claims

that he doesn't

need the money and that the important thing is to "do my

thing." And that

he has always done, regardless of whether it had an

audience or not. He

continues to think of himself as "an artist-in-residence,"

whether at a

university or a television network. It's all the same to

him as long as

he is free to work unencumbered.

Still, he is pleased to be with NET, pleased with the new attention being paid him, pleased with the success of Sesame Street, another trail blazer seen on NET stations, and happy to be back in the larger public eye.

"I asked myself who in his right mind would go back into television any more - except to make a bundle?" says Tillstrom, assuming his most ferocious Oliver J. Dragon-like stance. "Not that I don't I like to be paid, but it's all economics! Take the Money and Run. Ugh! The real question is what can we do for people? Then I thought maybe that question will come back into fashion again. After all, we are talking about the most powerful communications force the world has ever known."