By HELEN BOLSTAD

By HELEN BOLSTAD

O NCE UPON A TIME, in the city of Chicago, on a spring evening in 1936, a high school boy came to a dancing star's dressing room bearing a parting gift for the ballerina who had become, to him, the personification of all loveliness. Night after night, during that Ballet Russe engagement, Burr Tillstrom had watched Tamara Toumanova float through the enchanted "Swan Lake" or "Las Sylphides." Going backstage to meet her, he had found her more than gracious. As their acquaintance grew into friendship, he had told her of his dreams and ambitions.

"Certainly, I'd like a stage career," he had confided, "but, gosh - I want to eat regularly, too. Now that I've won a scholarship to the University of Chicago, I had better become a teacher," he said earnestly. Yes, he had acted in school plays, he added, but somehow he always seemed to get the role of an old man, balding and querulous. He found marionettes and puppets more to his liking.

Intrigued by his

description of the lively characters in his troupe,

Toumanova had

visited the Tillstrom home and tried her hand at making

them

perform. Because she enjoyed it, Burr decided to

give her a

puppet as a remembrance. It must, however, be a

special kind of

puppet - a companion to share her laughter, ease her

sadness, and to

talk to when she was lonely.

Intrigued by his

description of the lively characters in his troupe,

Toumanova had

visited the Tillstrom home and tried her hand at making

them

perform. Because she enjoyed it, Burr decided to

give her a

puppet as a remembrance. It must, however, be a

special kind of

puppet - a companion to share her laughter, ease her

sadness, and to

talk to when she was lonely.

Burr had made one creature he thought would suit. It was a hand puppet with balding bead, bulbous nose and a quizzical look - almost a self-portrait of Burr himself in one of his old man roles. He had intended it for another puppeteer. But, when he had it packed, ready to ship, he had so hated to part with it that he sent another figure instead. Now, because it was his favorite, he would give it to his adored Toumanova.

From the first moment that she saw it, he wanted it to have animation - so, on meeting her, he directed, "Close your eyes. I've got a surprise." In a moment, he was ready. "Now open them."

As the ballerina turned and looked, the figure tilted its head flirtatiously. She laughed with delight. "Kukla!" she cried.

Burr liked the sound of the word, "What does it mean?"

"It's Russian for doll," Toumanova explained. "It's the Greek word, too. But there's more meaning - I just can't express. It's any precious little thing."

The puppet had found a name - and, instantly he seemed to come alive. With an independence of his own, he danced and strutted. To Burr, it was strange, exciting and a little terrifying. He realized he could no more give Kukla away than he could give away the hand on which Kukla rested. The creature had ceased to be a puppet and had become part of him.

That was the turning point in the life of Burr

Tillstrom. Because of Kukla, the puppet who twice

refused to

leave, Burr's term at the University of Chicago was

brief. Kukla

so demanded to be seen that Burr gave up his plan to

teach. The

next time Toumanova met them - during their vacation in

1951 - she was

starred in the Paris opera, but Kukla had a whole

company of his own

and Burr Tillstrom, that erstwhile schoolboy, had

become, thanks to

television, the most famed puppeteer of our day.

That was the turning point in the life of Burr

Tillstrom. Because of Kukla, the puppet who twice

refused to

leave, Burr's term at the University of Chicago was

brief. Kukla

so demanded to be seen that Burr gave up his plan to

teach. The

next time Toumanova met them - during their vacation in

1951 - she was

starred in the Paris opera, but Kukla had a whole

company of his own

and Burr Tillstrom, that erstwhile schoolboy, had

become, thanks to

television, the most famed puppeteer of our day.

He had changed little in the passing years. Time touches him lightly. Blond, gray-eyed, wiry in build, and now in his mid-thirties, Burr Tillstrom could still tuck a notebook under his arm and blend into a bunch of sophomores on any campus. More important to Kukla, Fran and Ollie is the fact that he also retains intact that youthful ability to wonder and to see everyday things as though he were discovering them for the first time.

Burr's imagination flows freely, his interests are wide, and he seeks new information wherever he goes. While spending summers at Nantucket, he gathered a fund of whaling lore to rival that of the oldest inhabitant. Going to Ohio State university to receive an award from its Institute for Education by Radio-TV, he surprised the educators by also attending their lectures. When accepting their trophy, he advised (via Oliver J. Dragon): "My suggestion to you kids is to dip into show business. Get a little bit of both humor and education into your shows and you'll attract a bigger audience."

Having qualified for membership in Mystery Writers of America - thanks to Ollie's fondness for playing "detec-a-tive" - he once went to a party in honor of Anthony Boucher, who reviews mystery books for the New York Times and also edits a science-fiction magazine. Shortly, the two retired to a quiet corner, first, to swap Sherlock Holmes opinions, and second, to discuss learnedly plans for a space ship. Accounting for his technical knowledge of rocket propulsion, Burr explained, "Buelah Witch has been studying up on outer space travel."

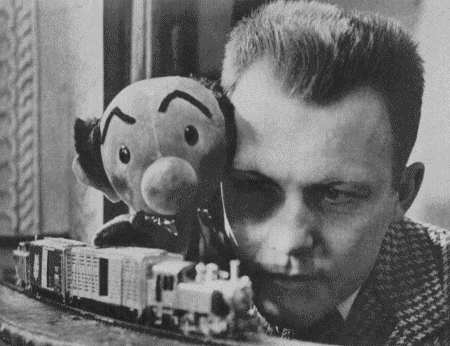

He has many skills. He can work a piece of wood

as deftly as a carpenter. As a sculptor shapes

clay, Burr can

combine cloth, padding, buttons, a bit of hair and some

paint to

construct a puppet. He also can cook, sail a boat,

and swim like

a fish. He once rode a bicycle across Canada's

rugged

Gaspé Peninsula. During recent vacations he has

divided his time

between Nantucket and Europe. He's a fan of

music, ballet,

archeology and model railroads.

He has many skills. He can work a piece of wood

as deftly as a carpenter. As a sculptor shapes

clay, Burr can

combine cloth, padding, buttons, a bit of hair and some

paint to

construct a puppet. He also can cook, sail a boat,

and swim like

a fish. He once rode a bicycle across Canada's

rugged

Gaspé Peninsula. During recent vacations he has

divided his time

between Nantucket and Europe. He's a fan of

music, ballet,

archeology and model railroads.

Because equipment and trophies relating to these varied pursuits long ago overflowed the apartment which be. shares with his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Bert Tillstrom, Burr lives in two places. The family occupies a large apartment in a new cooperative building on Chicago's Near Northside. Also, as Burr says, "Kuke and Ollie have the coach house."

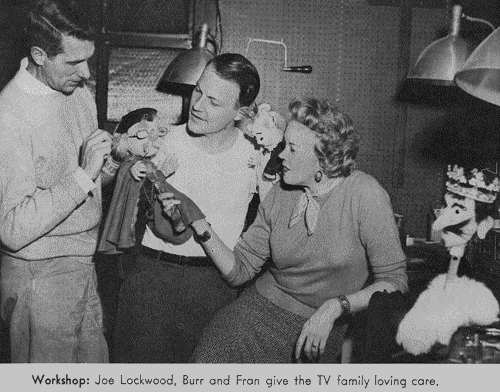

The coach house stands at the rear of what was once one of the city's great mansions. Aided by his backstage assistant, Joe Lockwood, who is an interior decorator and designer, Burr planned the remodeling and did some of the work himself. The ground floor, which faces a small garden, is his workshop. A well-equipped bench stretches across one wall. Miniature stages cover another, and a large area is kept open for whatever project is under way.

The second floor was once the mansion a ballroom. Burr built a compact kitchen, complete with dishwasher, into one corner. Opposite are two couches, set at right angles. A grand piano stands in the nook made by the staircase. Two sofas are placed in front of a huge fireplace and there is a wide, low table between them. Walls are white, rugs are off-white, and upholstery and woodwork are brown. It's a pleasant place for a large party, and it's a second home for most of the Kuklapolitan staff. There they often gather to work out songs, study the kinescopes of the show, or just settle down to have a quiet dinner together.

Bachelor though he is, Burr has become, in effect, the head of a large family - for the association of the staff, off-stage, is as close-knit as that of the Kuklapolitans on-stage. Four of its key members - co-star Fran Allison, producer Beulah Zachary, director Lewis Gomavitz and special assistant Joseph Lockwood - have worked with Burr ever since the show first went on the air at Station WBKB on Burr's birthday, October 13, 1947.

This close association permits Kukla, Fran And Ollie to remain a spontaneous program. Each person knows exactly what to expect from another. They also know how each of the Kuklapolitans can be expected to react under any given set of circumstances. Program planning starts with a huddle. Burr, Fran and Beulah will get an idea. Gommy and Joe will suggest props. Carolyn Gilbert will think of music which fits in. Only the music is rehearsed. As informally as this, they go on the air.

Those unfamiliar with the show always ask, "How many people do the voices?" The direct answer is, "One - Burr Tillstrom." Those who work on the program do not think in those terms, however. They speak of "what Kukla does," "what Ollie will do" - though never forgetting for a moment that it is Burr who is solely responsible for getting them to do it at the right time.

There is no need for a script writer, for Fran ad-libs better conversation than anyone could write, and Burr has been putting words and voices into his characters' mouth - and distinct personality into their being - all his life.

Dramatizing a story was a thing Burr learned

from his parents. As young people in Benton

Harbor, Michigan,

Bert and Alice Tillstrom enjoyed appearing in home

talent shows.

When they moved to Chicago, they continued their

association with

amateur theater groups.

Dramatizing a story was a thing Burr learned

from his parents. As young people in Benton

Harbor, Michigan,

Bert and Alice Tillstrom enjoyed appearing in home

talent shows.

When they moved to Chicago, they continued their

association with

amateur theater groups.

While still a toddler, Burr made his teddy bear and toy elephant act out songs his mother sang. At an age when other kids constructed scooters, he turned an orange crate into a miniature stage.

His father helped Burr endow speechless creatures with personality. The family spent summers at Benton Harbor and, as soon as Dr. 'Tillstrom arrived for weekends, Burr and his older brother, Dick, demanded stories. Some the father read from Alice in Wonderland and The Wizard of Oz. Others he made up as he led the boys on long rambling walks through the open country. Creatures took on character. A scurrying rabbit was a messenger carrying important news. A bird's song had words. The seldom-used track, meandering along the creek bed, became "the pumpkin vine railroad." Burr recalls, "Everything had personality - and two personalities made a plot."

Returning to the city, Burr imparted to his toys the characteristics of his country friends. An understanding teacher noting his talent, showed him how to construct puppets and marionettes.

Then came a chain of circumstances which inevitably turned Burr Tillstrom into a puppeteer. The first was pure luck. The Tillstrom moved into an apartment across the street from Mrs. Charlotte Polak, sister of the great puppet master, Tony Sarg. Lugging one of his own marionettes, Burr went calling. "Soon we kids were staging shows in Mrs. Polak's garden, under her direction," says Burr. "What's more, we charged admission. It was only a few cents, but I felt real professional."

Further opportunity to study new techniques came through seeing the puppet shows at the Century of Progress world's fair in 1933 and attending the American Puppetry Festival in Detroit in 1936.

The final swing away from his plan to become a teacher was brought about by the offer of a WPA job. He was already a freshman at the University of Chicago, trying to forget about his puppets, when the offer came. The Chicago Park District, acting jointly with the WPA, had determined that they could best provide work for unemployed theater people by setting up a marionette project. Few, however, knew anything about the techniques. Because Burr already had done volunteer shows for the Park District, they sought him out as an experienced puppeteer.

The offered salary, while small, seemed to Burr much more attractive than continuing to take a schoolboy's allowance, for the Tillstroms - while far from being on relief - were, like everyone else, feeling the pinch of the Depression. Temporarily (he thought) Burr quit the University and joined the company.

During this period, Burr began his first

serious experimenting with hand puppets and liked

them. While

marionettes - maneuvered by strings according to set

plot - must follow

a narrator's script, the hand puppets allowed him

spontaneous

expression. The best of them, of course, was

Kukla, the fellow

who twice refused to be given away. Burr took to

carrying him

around in his pocket

During this period, Burr began his first

serious experimenting with hand puppets and liked

them. While

marionettes - maneuvered by strings according to set

plot - must follow

a narrator's script, the hand puppets allowed him

spontaneous

expression. The best of them, of course, was

Kukla, the fellow

who twice refused to be given away. Burr took to

carrying him

around in his pocket

Difficult as it is for any televiewer to imagine it today, during all this period Kukla had no voice. The marionettes were the stars, and Kuke, at best, was only a between-acts pantomimist. Then an extremely arty reduction of "Romeo and Juliet" was scheduled. Burr, who knew the role letter-perfect, wanted to play Romeo. He ended up, however, the most frustrated Shakespearean in Chicago, for his sole assignment was to turn pages of the narrator's script.

B urr took the disappointment politely, but it was too much for Kukla. Out he popped, during rehearsal, and in a sweetly innocent voice - reminiscent of one of the little animal characters in Dr. Tillstrom's long-ago stories - Kukla took up Romeo's romantic lines. He sighed for love, and mourned his cruel fate. Then, departing Shakespeare's lines, he went on to speak of what he thought the arty producer was doing to Shakespeare. Things well-mannered Burr would never say rattled in sharp-barbed comment from Kukla. Says Burr, "I guess some of the rest of the cast must have thought the same way, for they all started to laugh and Kukla was a riot."

From that time on, Kukla became an impromptu entertainer at parties. People would ask him questions, and, as Burr says, "Kukla was real smart with people. When I was too young or too ignorant to have an answer, Kukla took over. What would have been naive, coming from me, sounded funny coming from Kukla."

While Kukla sprang to life instantaneously and has changed little, Ollie originated most modestly but has grown like Jack's beanstalk. Traditionally, all puppet shows had a dragon, usually a terrible creature with a picket-fence of gnashing teeth. Burr had a different idea. He says, "I wanted one which would not scare even the most timid child. So Ollie got what he now calls his 'prehensile tooth.'"

Ollie's opportunity to display that tooth came

primarily during appearances in the children's theater

at Marshall

Field's department store. During those lean years,

Burr worked

Mondays through Fridays as a sales clerk.

Saturdays, with his

mother playing the piano, they put on a show to baby-sit

with children

while parents shopped.

Ollie's opportunity to display that tooth came

primarily during appearances in the children's theater

at Marshall

Field's department store. During those lean years,

Burr worked

Mondays through Fridays as a sales clerk.

Saturdays, with his

mother playing the piano, they put on a show to baby-sit

with children

while parents shopped.

It was at Field's too, that Burr discovered television. An RCA demonstration unit arrived there in 1939. Burr took one look at what happened with screens and cameras and knew this was what was needed to present Kukla, Ollie and his other little people as life-size. With a card table as a stage, he did his first show. Neither Field's nor RCA executives were impressed. Says Burr, "The engineers saved us. They fell in love with Kukla. The guys who keep things running always like Kukla."

With that introduction, Burr became one of television's pioneers. In 1940, RCA had him do the first ship-to-shore telecast, then made his show a feature of their exhibit at the New York World's Fair. Two important developments then occurred: Kukla set the pattern of working with people, and Ollie found his voice and character.

Kukla, it should be recalled, learned to talk to human beings as early as 1936. Says Burr, "It's taken for granted now, for every puppet show has copied us, but it was then unorthodox to combine puppets and people. Playing those ten shows a day at the World's Fair, we were always introduced by a pretty girl. Naturally, Kukla couldn't be suppressed and so the girl-and-puppet combination became a definite routine in 1940. Later, during my short stints in vaudeville and a few night clubs, I continued to use a live person out in front. Now it seems natural - but, as an actual fact, we were the first to bring it into the world."

It was the VIP visitors to that RCA exhibit who endowed Ollie with personality. Says Burr, "We did take-offs, kidding the press, visiting dignitaries and friends, through Ollie. One performance, he'd be a newspaper man, another an engineer, a famous singer or a big shot from the industry. That's where he found out he could do anything and be anybody."

Ollie's first major triumph came at the end of that season. Burr recalls: "Two close friends, who also worked at the Fair, wrote 'St. George and the Dragon' as a satire of the legend, with Ollie the hero. After that, there was no holding him. He has grown to be Oliver J. Dragon, baritone, son of Mrs. Olivia Dragon of Dragon Retreat, Vermont, first cousin and guardian of Doloras Dragon, and a great authority on all dragon lore.

Fran joined up at WBKB. When, at the end of the war, commercial television came in, Burr was ready for it. Captain William Crawford Eddy, then head of the Balaban & Katz-Paramount station in Chicago, offered Burr the first sponsored, hour-long, five-day-a-week program.

For years,

Burr had dreamed of this. This was his

chance. But it also

was his chance to fall flat on his face, for Eddy -

entranced with the

Kuklapolitans and impressed by Burr's own great charm

suggested that

Burr do everything, including coming out in front to

interview child

guests and to do the commercials,.

For years,

Burr had dreamed of this. This was his

chance. But it also

was his chance to fall flat on his face, for Eddy -

entranced with the

Kuklapolitans and impressed by Burr's own great charm

suggested that

Burr do everything, including coming out in front to

interview child

guests and to do the commercials,.

Burr, recalling that conference, grins. "I suppose it was our best compliment, for it indicated that the Kuklapolitans were so real to him he actually thought of them as being self-animated. I almost hated to explain that they, too, kind of needed me, backstage. Our producer, Beulah Zachary, and our director, Lewis Gomavitz, were sitting in on that huddle and, for a while, we hassled the problem back and forth. Then, rather than bring in an additional puppeteer or a fancy production staff, I suggested we revert to what I had already proven would work - we decided to have a live person out in front. Gommy suggested Fran Allison, and that suited me."

Fran, who already was well known on the ABC Breakfast Club, proved to be gentle with Kukla and understanding with Ollie, but it was a tangle with Mme. Ooglepuss - that character who deems herself an unfading beauty - which made the situation jell. The Madame, during one of the first telecasts made some acid remark about Fran's hair. Fran's retort was quick, "Well, at least mine's real."

Burr defines her importance. "It's Fran who gives the Kuklapolitans reality. Because she talks to Kukla, Ollie and the others exactly as she would to humans, the viewers, too, regard them as real."

The Kuklapolitans have lived with zest on television. The troupe now includes Mme. Ooglepuss, Buelah Witch (who borrowed her name from Producer Beulah Zachary and changed the spelling just to be different), Fletcher Rabbit, the mailman; Cecil Bill, the stagehand; Mercedes, the teenager; Col. Cracky, Southern gentleman; Doloras, Ollie's niece; and, occasionally, Olivia Dragon, Ollie's mother. Once in a blue moon, that trouble-maker, Clara Coo Coo, flies in from North Pole

It's a tribute to Burr's mastery of

make-believe that everyone connected with the show

regards it as a

distinct breach of etiquette ever to refer to these

well-developed

characters as "puppets." Collectively, they're

"the kids," and,

individually you address them by name.

It's a tribute to Burr's mastery of

make-believe that everyone connected with the show

regards it as a

distinct breach of etiquette ever to refer to these

well-developed

characters as "puppets." Collectively, they're

"the kids," and,

individually you address them by name.

The Kuklapolitans could fill a book with the fabulous adventures they have had since that winter of 1947 when there were only three hundred fifty-three television sets in Chicago, five stations on the air in the entire United States, and no coaxial cable or networks at all. They have made friends with millions of viewers, acquired celebrities as their fans, vacationed in Europe, appeared with the Boston Pops Orchestra to do their now-enhanced "St. George and the Dragon," and staged a concert of their own in New York's Town Hall.