The

day before,

when they had done their version of The Mikado,

everything had gone

very well, even Ollie's entrance as Lieutenant Pinkerton

(somehow he had

got the idea that they were doing Madame Butterfly).

Now Burr

and Fran and Beulah and Lew were sitting around

wondering what to do on

that afternoon's show. Burr said he thought the

kids might talk over

their performances of the day before. Fran said

she thought a post-mortem

might be funny - everybody could be very sweet at first,

she said, and

wind up battling. Beulah and Lew agreed, and the

four of them went

to talk to Jack, who was in the studio sitting at his

piano. Joe

came in then, heard what the show was going to consist

of, and went backstage

to fuss with some props. With no more preparation

than that, another

episode of

Kukla, Fran and Ollie was ready to go out to

about five-million

television sets.

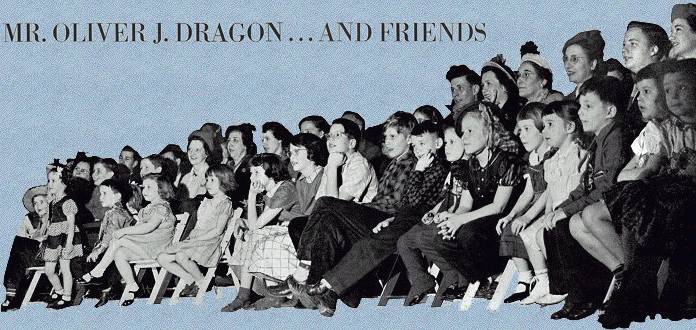

For the benefit of hermit subscribers, it should be

explained here that

Kukla,

Fran and Ollie is a sensationally successful

television show currently

being shown on about sixty stations. The people

mentioned above need no

introduction; but, again for the hermits, here is who

they are. Burr

is Burr Tillstrom, a quiet, blue-eyed puppeteer in his

early thirties.

Fran Allison is a tall, slender, grey-haired girl who

talks to Burr's puppets.

Beulah Zachary is the show's producer, Jack Fascinato is

the director of

music, Joe Lockwood is costumer and prop man, and Lew

Gomavitz is director

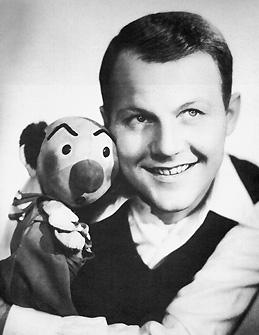

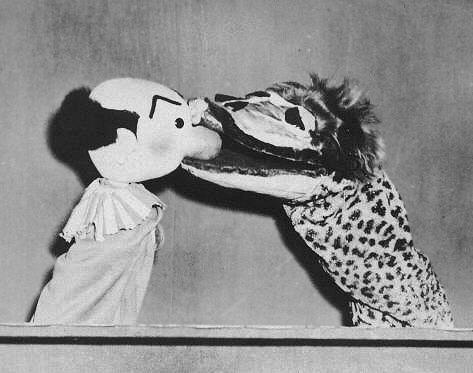

and all-around troubleshooter. Ollie is Mr. Oliver

J. Dragon, a gentle

member of his species who has soulful eyes, a single

tooth, and a body

that looks suspiciously like leopard skin. Ollie

modestly admits

to being the star of the show, but his claim is

sometimes disputed by admirers

of Kukla, the other puppet principal. Kukla is not

entirely sure

just what he is; once Fran told him that he was a

blessing, and although

he settled for that, the question of identity still

bothers him occasionally.

In appearance he somewhat resembles a small boy,

although he is bald and

has a nose like a bright red doorknob.

For the benefit of hermit subscribers, it should be

explained here that

Kukla,

Fran and Ollie is a sensationally successful

television show currently

being shown on about sixty stations. The people

mentioned above need no

introduction; but, again for the hermits, here is who

they are. Burr

is Burr Tillstrom, a quiet, blue-eyed puppeteer in his

early thirties.

Fran Allison is a tall, slender, grey-haired girl who

talks to Burr's puppets.

Beulah Zachary is the show's producer, Jack Fascinato is

the director of

music, Joe Lockwood is costumer and prop man, and Lew

Gomavitz is director

and all-around troubleshooter. Ollie is Mr. Oliver

J. Dragon, a gentle

member of his species who has soulful eyes, a single

tooth, and a body

that looks suspiciously like leopard skin. Ollie

modestly admits

to being the star of the show, but his claim is

sometimes disputed by admirers

of Kukla, the other puppet principal. Kukla is not

entirely sure

just what he is; once Fran told him that he was a

blessing, and although

he settled for that, the question of identity still

bothers him occasionally.

In appearance he somewhat resembles a small boy,

although he is bald and

has a nose like a bright red doorknob.

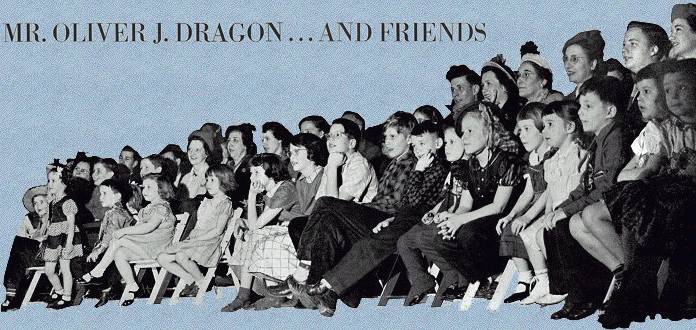

Story conferences and preparations for any day's presentation of Kukla, Fran and Ollie are seldom more elaborate than those described in the first paragraph. No frantic sponsors, nail-bitten gagmen, or ulcerous advertising agency executives intrude upon the quiet meetings that are held in the afternoons in three small rooms in the NBC studios on the 19th floor of Chicago's Merchandise Mart; no script has ever littered the floor. Burr Tillstrom and his associates simply talk over their program and then they go and do it; it is no more complicated than that. Once an agency man suggested to Burr that he could use a writer; Burr stared at him a moment and left the room. Beulah, who has steel-grey hair and a temperament to match when the occasion demands, has spent large portions of her time reading the riot act to assorted Philistines who have insisted, sometimes bluntly and sometimes insinuatingly, that the show could not last without formalization. She has always won her battles; Kukla, Fran and Ollie is not only not formalized, it is perhaps the most blithely informal program on the coaxial cable. It won sixteen awards in 1949 alone; the kids (Burr never refers to his puppets as puppets) are national figures and Fran's admirers would more than fill the Chicago telephone directory.

To those remaining humans in the United States who have

never seen this

show, the idea of a girl talking to an assortment of

puppets may not sound,

at first, like an exciting one. Yet that is

substantially all that

happens. Kukla and Ollie come on stage, talk for a

while, and ultimately

are joined by Fran. Sometimes Kukla and Ollie give

way to one of

the other characters: Cecil Bill, the stage hand, whose

squeaks and twitterings

are intelligible only to Kukla; Madame Ooglepuss, a

red-haired lady with

a horribly crooked nose and the manner of a grande dame;

Colonel Cracky,

a Southern gentleman; Fletcher Rabbit, the postman, who

sometimes starches

his floppy white ears; the naughty Mercedes, Clara Coo

Coo, or Buelah Witch.

All the Kuklapolitans have strong, identifiable

characters; each of them

represents facets of the collective human

personality. There is not

as much slapstick as one ordinarily expects of a puppet

show.

To those remaining humans in the United States who have

never seen this

show, the idea of a girl talking to an assortment of

puppets may not sound,

at first, like an exciting one. Yet that is

substantially all that

happens. Kukla and Ollie come on stage, talk for a

while, and ultimately

are joined by Fran. Sometimes Kukla and Ollie give

way to one of

the other characters: Cecil Bill, the stage hand, whose

squeaks and twitterings

are intelligible only to Kukla; Madame Ooglepuss, a

red-haired lady with

a horribly crooked nose and the manner of a grande dame;

Colonel Cracky,

a Southern gentleman; Fletcher Rabbit, the postman, who

sometimes starches

his floppy white ears; the naughty Mercedes, Clara Coo

Coo, or Buelah Witch.

All the Kuklapolitans have strong, identifiable

characters; each of them

represents facets of the collective human

personality. There is not

as much slapstick as one ordinarily expects of a puppet

show.

The informality, although important, is not the main ingredient of the show's success. Television is perhaps the most personal and intimate of the visual media; its players, dropped as they are into the audience's lap, can't get by for long on sheer virtuosity. Burr and Fran have been successful not merely because they are artists but because they have been able to communicate their warmth and conviction clearly and strongly. Burr made the first Kukla about fifteen years ago. He was going to send it to a friend, but as he was packing the box he looked down at the little face and couldn't bear to send it away. Since then he has worn out eight Kuklas; they lie in a drawer in his workshop, sixteen button eyes staring up almost reproachfully. Each time Burr must make a new one, he feels a twinge of regret. So does Fran. Last year, when the show went to Washington for a week, Burr took a new Kukla; as they were starting out, Fran remarked wistfully that it was a shame that the old one hadn't got to make the trip. That was not a remark calculated for the fan magazines and the gossip columns; it was genuine feeling. Both Burr and Fran, quite literally, love and believe in the kids. They are her friends, they are his alter egos.

Fran, in fact, believes so implicitly in her fellow Kuklapolitans that it sometimes takes her a couple of days to get completely accustomed to a new version of one of them. Although she may not be wholly aware of it, Burr was originally directly responsible for her belief. When she first came to work with Kukla, Ollie, and their supporting cast, Burr had noted just the slightest touch of condescension in her voice. She understood the job she had to do, she was quick-witted and imaginative (few females have ever approached her gift for ad-libbing), but she wasn't quite right; she was thinking of the kids as puppets, not as beings with personalities of their own. Burr knew that he would somehow have to change her attitude without mentioning it to her, since pointing it out might have made her self-conscious. Accordingly, one day Kukla and Ollie (Burr is the voice and manipulator of all nine puppets) began talking about female habits that were distasteful to men. They talked gently and reservedly, not speaking directly to Fran, but they managed to touch her femininity, and within a few minutes she was defending her sex spiritedly. From that program on, she was never condescending again.

Kukla, Fran, and Ollie started out as a show designed

for children.

It's difficult to decide, today, whether it is still

that; it could be

called a children's show for adults, or an adult's show

for children.

Like Alice in Wonderland, to which it has been compared

on many occasions,

it is for everybody. Actually, it is not much

different from impromptu

shows that Burr used to give for friends at parties

around the time when

he first made Kukla (Toumanova, the ballet dancer, named

the little fellow;

"Kukla" is Russian for "doll"). At that time,

Kukla simply commented

on things that were on Burr's mind; Burr was in a

theatrical group, and

Kukla used to criticize the actors' performances.

It is the same

today. Kukla, Ollie, Madame Ooglepuss, Colonel Cracky,

Buelah Witch and

the rest simply talk about things on Burr's mind.

Once he and Fran

and the kids were invited to Pleasantville, New York, to

visit the Reader's

Digest crowd. They were given a kind of Royal Tour

and taken in to

see the desk where Lila Acheson Wallace has her creative

spasms.

Later they gave a show for the manorial hired

hands. "What magazine

did you say this was?" Ollie whispered to Kukla,

"Coronet?"

Stray

thoughts, fragments of ideas, letters or gifts from fans

- anything

that touches Burr's being ultimately comes out as a

show. He likes

to read science fiction; Ollie does too, and sometimes

discourses on atomic

energy or galactic war. Burr loves to go to

parties; the Kuklapolitans

are always discussing good times they had at parties the

night before.

When I first went to Chicago last summer to meet Burr

and gather material

for this piece, he misunderstood my name and called me

Bob; he continued

to do so until another friend corrected him. On that

day's show, Fran invited

Ollie to go with her to a carnival. "I can't," he

said, "I have a

dinner engagement. A fellow is here to write a

magazine story about

me." Fran asked what the fellow's name was.

Ollie hesitated.

"Why, ah, it's-uh-Bob," he finished, triumphantly, and

vanished downstairs

to his dressing room.

Burr has even used adverse criticism as material for a program. Philip Hamburger, The" New Yorker" television columnist, once expressed some reservations about Kukla and Ollie (thereby prompting Deems Taylor, among others, to wire Burr, HAMBURGER DOESN'T KNOW HIS ONIONS). The day the article appeared, Kukla lugged "The New Yorker" up on the stage, and he and Ollie read the piece together. They quietly agreed that Hamburger had a perfect right to his own opinion, managing in the process to get across the idea that it was just possible that he wasn't very bright. That program ended with a wrestling match; Ollie had suggested that Hamburger might like that kind of entertainment better.

Above, I nearly wrote that Ollie frowned. Such is Burr's artistry; the faces of his fist puppets, of course, do not change. But their voices are so expressive, their movements so well articulated; that after a few minutes of watching the show one forgets - as indeed Fran has demonstrated - that they are not actual persons. Even Burr is captured by the illusion; one day he produced a record and said he wanted me to hear what happened when Ollie lost his hair (Kukla had been experimenting with a permanent-wave machine). All through the show, sitting on the floor by the phonograph, Burr seemed to be hearing the voices for the first time; it was as though he were a total stranger who had had nothing to do with the performances.

Burr's whole concept is theatrical. He is now thirty-two, and has been stage struck since the days when he first began giving voices to his Teddy Bears and other toys. He was encouraged by his mother, who plays the piano, and his father, Dr. Bert Tillstrom, a foot specialist who used to tell Burr and his brother stories while hiking in the country. Burr appeared in plays in high school, where he specialized in dramatics, and later won a scholarship to the University of Chicago. The grim logic of that rational institution was too much for him, and he left after his first semester. He worked with WPA theatricals and in various local groups, and although he sometimes clerked in a department store and did other odd jobs, he never considered anything but the theatre as a career - which, of course, is why the Kuklapolitans never pretend to be anything but actors. Burr's conversation is liberally sprinkled with the idiom of the stage ("Oh," he says of Fran, "she's so great, so wonderful"), and Kukla and Ollie, in turn, sometimes sound like actors on the late shift at Sardi's. They are constantly giving their own versions of shows, usually musicals; no show in existence is as lavishly costumed as theirs. Behind their stage are two huge metal cabinets full of costumes, four equally huge ones containing props, and two twelve-foot shelves groaning under a fantastic array of instruments, devices, and scenery. Burr makes most of the equipment of the show, but large quantities are sent in by the audience. Buelah Witch, for example, has an ermine cape given by an admirer (Buelah was named after Beulah Zachary, but resembles her only in name). Forty people have knitted cold-weather nose cosys for Kukla. A dentist once sent Ollie a hand-made set of wooden teeth. The hats alone used on the program would make Ed Wynn turn green, even on black-and-white video.

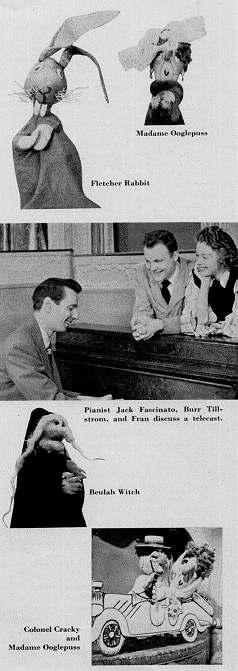

Offstage, Burr is a relaxed, casual, quiet young man

with small bright

eyes and a boyish smile. He usually wears a crew

cut but sometimes

lets his brownish hair get long enough to comb back and

to the right.

He likes to go on bicycle trips and is a good swimmer;

in summer, he and

Beulah and Lew and Fran and the rest often hold story

conferences on the

rocks along Chicago's endless lakefront. Burr

lives with his parents

in an unpretentious apartment out Evanston way. He

spends most of

the morning and early afternoon hours in his workshop,

where he is currently

working on marionettes for a soon-to-be produced version

of The Wizard

of Oz; when he gets tired of working he wanders

upstairs and talks

to a three-inch green parakeet who knows that his name

is Buster Tillstrom,

can whistle the Kukla, Fran, and Ollie theme,

and can tell when

it's time to go to bed. Burr has never quite

become accustomed to

the fact that he is a celebrity. Last year in New York a

friend took him

backstage at South Pacific to meet Mary Martin

and Ezio Pinza.

Miss Martin, an ardent Kukla, Fran, and Ollie

follower, overwhelmed

him with questions about the kids, and Pinza confided

that he had had to

buy a second television set because, as he explained

sadly, his children

had deserted the Kuklapolitans for another show that

came on at the same

time. Burr, who had just been bowled over by the

Pinza-Martin performances,

could scarcely grasp what was going on; for one

frightened moment he thought

they were ribbing him. When celebrities in other

fields write Kukla

and Ollie letters of unashamed devotion, Burr still

wonders if there hasn't

been some mistake.

Although he could hardly be called shy, Burr is diffident and unassuming to a degree seldom achieved by theatrical folk. Mostly he stays with a small knot of friends, talking about almost everything but his own activities. His reticence vanishes the instant he gets be hind the Kuklapolitan stage, where he is commanding and sure, a master at his work. He operates standing erect, behind a translucent screen, resting his puppet-clad arms on a ledge and keeping his eyes to the right, watching a tiny monitor-screen that shows him what the kids and Fran are doing out front. He has developed an incredible dexterity in changing from one character to the other. The kids hang heads downward on little hooks under his arm-rest; when one of them comes off stage, Burr slips a small loop at the bottom of the puppet's costume onto a hook, pulls out his arm, and shoves it down into the body of the next character awaiting a cue. Joe Lockwood, standing behind him, dresses the kids as they are waiting to go on and hands over props as needed.

Burr's active interest in puppetry dates from the year he was fourteen, when a sister of the famous Tony Sarg encouraged him to construct marionettes of his own. In the mid-Thirties he worked with the Chicago Parks District Theatre and later took his act into carnivals, fairs, and night clubs. In 1939, just as he was all set to go to Europe with a marionette troupe, he was offered a chance to put on a weekly Saturday morning puppet show for children at the Marshall Field department store. He stayed in Chicago and ultimately did the first Balaban and Katz telecast over Station WBKB in 1941. That convinced him that television was the medium in which he could work at best advantage. When he first began doing a series in 1947, the sponsors wanted an hourlong program. Astonished at being offered so much time, Burr declared that he couldn't work alone - but at the same time, the idea of anybody else manipulating his own creations was unthinkable. He thereupon got in touch with Fran - who was then, as she is now, doing the Aunt Fanny part on Don McNeil's Breakfast Club. Fran, an Iowan, had been a schoolteacher before coming to Chicago, which may account in part for her patient, easygoing manner and her understanding of Burr's kids. She, Kukla, Ollie, and the rest got along very well from the beginning. The original sponsor, RCA, has been supplemented by two more, Sealtest and Ford; last year the show moved to WNBQ, the NBC outlet in Chicago.

Burr and Fran have never regarded their program as

anything but an occasion

for fun. He is constantly trying to throw her a

line that will catch

her off guard; quite often just the reverse happens

("She breaks me up

all the time," he says, happily). Fran has

contributed a great deal

to the Kuklapolitans' genealogical background. One

day Ollie, an

alumnus of Dragon Prep, asked Kukla if he happened to

know where Buelah

Witch had gone to school. Kukla didn't know, but

Fran did.

"Why, she went to Witch Normal," she said. Shortly

after that, Beulah

Witch began mentioning her days at Witch Normal with

increasing nostalgia,

and to date the school has been equipped with a faculty

and a set of rigid

traditions.

Burr and Fran have never regarded their program as

anything but an occasion

for fun. He is constantly trying to throw her a

line that will catch

her off guard; quite often just the reverse happens

("She breaks me up

all the time," he says, happily). Fran has

contributed a great deal

to the Kuklapolitans' genealogical background. One

day Ollie, an

alumnus of Dragon Prep, asked Kukla if he happened to

know where Buelah

Witch had gone to school. Kukla didn't know, but

Fran did.

"Why, she went to Witch Normal," she said. Shortly

after that, Beulah

Witch began mentioning her days at Witch Normal with

increasing nostalgia,

and to date the school has been equipped with a faculty

and a set of rigid

traditions.